St. Augustine civil rights sites: Martin Luther King and the ‘Splash Heard Around the World’

There’s no escaping history in St. Augustine, Florida. Founded in 1565, it proudly calls itself the oldest continually occupied European city in North America. For more than a century, it has banked on that past, drawing tourists to its archaeological sites, ancient forts and museums.

But one bit of history is often overlooked.

In the 1960s, Martin Luther King came to St. Augustine, rallying hundreds of civil rights protesters, who faced violence on the streets, while Congress debated the Civil Rights Act in Washington.

The St. Augustine Movement developed partially in response to a birthday. The city planned to mark its 400th anniversary in 1965 with new projects and tourism promotions. But the local Black community objected that the city’s schools and businesses remained segregated, and that citizens remained locked out of jobs and opportunities.

‘St. Augustine should be on any civil rights travel itinerary, with history just as compelling and consequential as Greensboro, Selma and Birmingham.’

In 1964, protesters marched through the Florida city, faced off with the Ku Klux Klan and white mobs, and waded into the ocean to challenge segregated beaches. It’s also the site of the largest arrest of U.S. rabbis, who came to support King. Finally, the city found itself making national headlines when an irate hotel owner poured acid into a swimming pool with Black and white swimmers — “the splash heard around the world.”

The image so shocked the world, that the next day the U.S. Congress finally passed the Civil Rights Act, outlawing segregation.

It’s surprising more people don’t know this history – just as compelling and influential as Greensboro, Selma and Birmingham. But slowly St. Augustine has begun to elevate its story. Visitors strolling through the Spanish Colonial city center – where slaves were once sold – will find monuments to civil rights foot soldiers. A prominent crosswalk is named for Andrew Young, a young aide to King who was beaten during a march. He went on to become the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations. And museums also explore the story.

So, by all means, St. Augustine should be on any civil rights travel itinerary. All of these sites except the beach are within a mile of each other, and can be easily walked. As a bonus, the northeast Florida coast is a wonderful vacation destination, with beaches, golf and great food.

The major sites include:

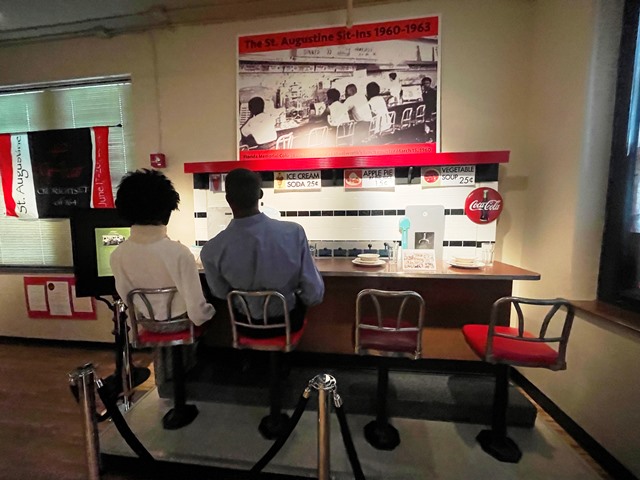

- The Lincolnville Museum and Cultural Center, exhibiting King’s original arrest record in the city, and the Woolworth’s counter that was site of a nationally recognized sit-in.

- Plaza de la Constitucion, home to the Foot Soldiers Monument, Andrew Young Crossing and footprints, and the “Slave Market.”

- The Historic Bayfront Hilton, former site of Monson Motel, which played a key role in protests when an owner poured acid in the pool

- The Accord Civil Rights Museum. Open by appointment only, this small dental office where NAACP leader Dr. Robert Hayling practiced was where King and others met.

- The Accord Freedom Trail offers an African American history walking tour of historic markers, most with ties to the protests.

- Potter’s Wax Museum window where a figure of Martin Luther King greets passing pedestrians.

- St. Augustine Beach Pier, site of wade-ins.

- Fort Mose, site of a free Black settlement from the Spanish colonial era.

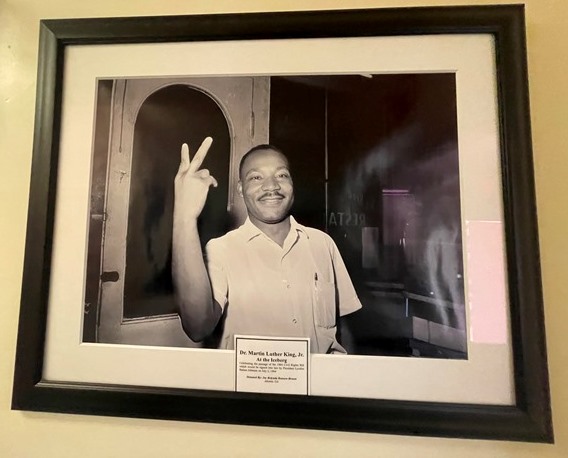

Lincolnville Museum and Cultural Center

Situated in the heart of the city’s first African American neighborhood, this museum and cultural center located in a former segregated high school is the best place to learn about the St. Augustine Movement and protests.

You’ll see King’s fingerprints on his arrest record, historic photos and images of the Ku Klux Klan and other segregationists that taunted the protesters. You’ll also learn about Marian Parkman Peabody, the mother of the governor of Massachusetts, who came to St. Augustine to get arrested during a protest.

Museum highlights include the Woolworth’s counter, where in July 1963, four high school students held a sit-in, and were arrested. When a judge offered freedom if they would agree not to protest, they instead chose reform school. The group, which became known as the St. Augustine Four, got national attention, with Martin Luther King and baseball great Jackie Robinson denouncing the punishment. After several months they were released, and two of the students even stayed with Robinson and his wife at their home in Connecticut.

Interestingly, two years early Hank Thomas, who was one of the original Freedom Riders, was arrested as a college student in 1960 for holding a one-man sit-in at a St. Augustine drug store. A judge tried to send him to a mental institution because he thought Thomas was insane. But he was bailed out by entertainer Sammy Davis Jr. Thomas attended the high school that now holds the Lincolnville Museum.

All this was a preluded to the protests that rocked St. Augustine in June 1964. You’ll get a surprising thorough overview from a video originally produced by the Florida State Patrol. This period film uses original news footage to explain the protest, and the police response. Although decades old and produced by the police, it still offers a firsthand account of St. Augustine in the midst of the protests. You’ll find the video near the bottom of this page.

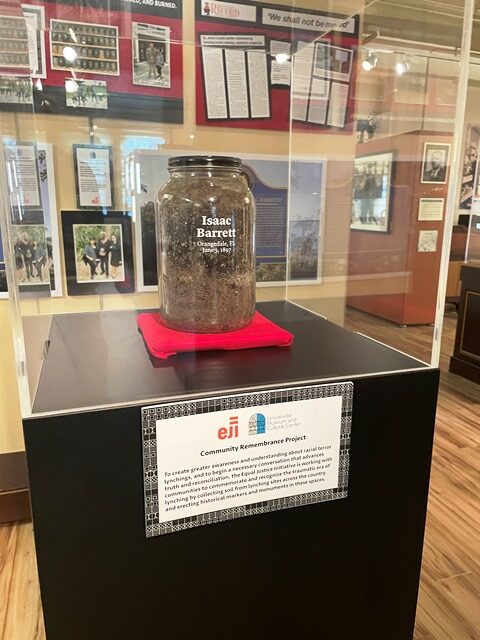

Other exhibits are devoted to the city’s rich history. But take time to notice the jar of soil taken from the site of the 1897 lynching of Isaac Barrett. It’s part of the national effort to memorialize and identify sites of racial terror spurred by the opening of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. Sadly, the historic marker noting the lynching was stolen from the rural site.

Plaza de la Constitucion

Like many Spanish colonial cities, St. Augustine is built around a central plaza. Naturally, this block is where protests converged, many focused on the still-standing open-air pavilion at the east end, where slaves were sold on several occasions. During one evening march, leader Andrew Young was attacked by a mob of white counter-protesters. He was knocked unconscious but got up and continued marching.

The site of the attack is now remembered with a monument showing bronze castings of Young’s shoes on the sidewalk. Each step is set off with quotes from Young, King and even President Johnson,

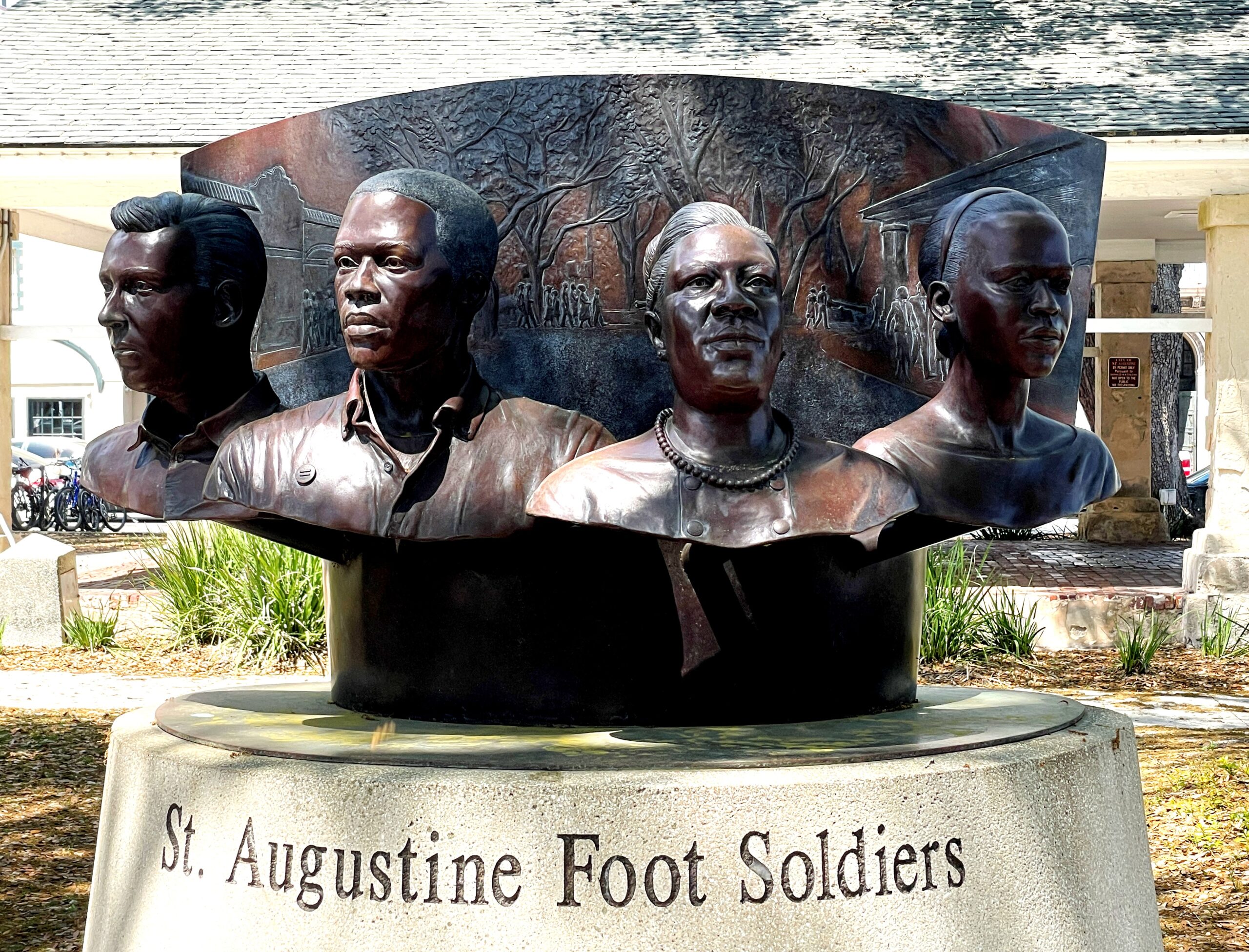

Next, head to the southeast corner of the plaza for the Foot Soldiers Monument, a bronze piece with four life-size heads representing anonymous protesters from 1964. The figures include a white college student, adult and teenage African American women and a young African American man,

Finally, cross King Street, and head over toward the intersection with St. George Street. You can see the original doors to the Woolworth’s, where sit-ins were held.

Historic Bayfront Hilton

A few blocks away, you’ll find one of the key protest points of the entire civil rights movement, the former site of the Monson Motor Lodge.

The segregated motel, which was owned by James Brock, the president of the Florida Hotel-Motel Association, became a flashpoint. While the hotel has been razed and replaced by a Hilton, it does preserve key sites of the conflict.

On June 18, 1964, white activist, Al Lingo, checked into the hotel, and invited Black protesters to join him in the motel pool to swim. The site of an integrated swimming pool so outraged Brock that he had an epic meltdown, and ran around the pool, pouring powdered muriatic acid into the water.

It became known as “the splash heard around the world.”

The picture was so haunting that it made front pages around the world. In fact, the day after the acid incident, the U.S. Senate finally broke its 83-day filibuster and passed the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

While the pool has been replaced, it’s in the same spot as the original. And while, it’s only open to Hilton guests, you can ask to look at an historic marker. From the front entrance, the pool’s located in the building directly in front of you to the left.

The former motel also has a surprising place in the history of Black-Jewish relations. During King’s protests, he wrote to rabbis requesting help in St. Augustine. Sixteen came and were arrested when they stopped to pray at the motel’s steps. You can see the steps and an historic marker just across the driveway from the entrance. Ask the valet, if you can’t find it.

Accord Civil Rights Museum

Dentist Robert Hayling was largely responsible for putting St. Augustine on the protest map. A leader of the Youth Council of the NAACP, he organized protests from his dental office, and joined with others to call on Martin Luther King to come to the city. Hayling faced danger when someone shot into his home, narrowly missing his pregnant wife and child, and killing his dog.

His former dental office at 79 Bridge Street now houses a small civil rights museum, open by appointment only. It’s worth taking the time to visit. Inside, you’ll see correspondence, historic photos and can visit the small room where the St. Augustine Movement was planned by SCLC leaders like King, Andrew Young, CJ Vivian, Fred Shuttlesworth, and many others.

To schedule a visit, call director Liz Duncan at 904-347-1382.

Accord Freedom Trail

While you’re in the Lincolnville neighborhood, you’ll notice historic markers in front of many homes. A website guides the way to homes and churches that played important roles in the protests. For example, next door to the Accord Civil Rights Museum stands a house where Martin Luther King stayed while he was in town.

King was supposed to have been based at a beach home that belonged to Christian missionaries, but the local newspaper printed the address and it was vandalized and shot before he arrived. Instead, he moved around the city, changing locations where he slept.

As one of the trail markers note, St. Augustine has one of the few Martin Luther King Boulevards in the country where King actually visited and stayed.

Potter’s Wax Museum

Here’s how to tell that St. Augustine is beginning to recognize its history. In 2016, one of its classic tourist attractions dedicated a figure of Martin Luther King. Its body is based on the mold of a local A.M.E. pastor, who agreed to model for the figure. Potter’s calls itself the oldest wax museum in he country. You can see the King figure from the sidewalk.

St. Augustine Beach

Segregation wasn’t limited to stores and schools. In St. Augustine and many cities, there were also Whites only beaches.

In June, 1964, an integrated group of about 30 activists converged on the beach by St. Augustine Pier for wade-ins, directly defying segregation. Some of the protesters couldn’t swim and nearly drowned when they were forced into the water by hostile crowds. You’ll find a marker at St. Augustine Beach Pier.

And nearby at 5480 Atlantic View, look for a marker in front of the vandalized home where King was supposed to have stayed.

Fort Mose

When Florida was under Spanish rule, it was a relative safe haven for enslaved people. For those trying to escape bondage in the Carolinas, an Underground Railroad led south to St. Augustine.

The Spanish welcomed the African-Americans as long as they’d covert to Catholicism and join the militia to defend the city. This community lived in Fort Mose, just north of St. Augustine. Although the fort itself is gone, a state park visitors center tells this fascinating story.

Guidebook

As a tourist city, St. Augustine has plenty to offer travelers. Travelers will love wandering its winding pedestrian streets lined with restaurants and shops. Its visitors bureau has lots of background and suggestions.

Where to eat in St. Augustine

Blue Hen Cafe: A delicious stop for breakfast or lunch, right across the street from the Lincolnville Museum and Cultural Center

Columbia Restaurant: A Florida classic for memorable Cuban food. The garlic shrimp and 1905 Salad, made tableside, are a sure bet.

Heart & SoulFood Truck: A Black-owned business with Southern favorites and Caribbean flavors. Check the website for its current location.

St. Augustine Seafood Company: Casual dining in the heart of the historic district with plenty of fresh-from-the-boat seafood.

Where to stay in St. Augustine

Homewood Suites: One of the city’s newest hotels. Walking distance of downtown, but away from the crowds.

Bayfront Hilton: Built on the site of the protests, it’s now modern and welcoming, and takes its historic role seriously.